Woven

Solo exhibition 2018

Tacit Galleries, Melbourne, Victoria.

Meaghan Shelton is fascinated by the processes by which knowledge is conveyed from generation to generation through embodied skills and traditional crafts. Her work considers the experiences of girls and women and how these experiences are communicated. Her making is about the making of experiences and stories and consequently, about the making of lives.

Perhaps no statement in any 20th century text has had as much impact on women as Simone de Beauvoir’s concise observation in The Second Sex (1949) that “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.” In this simple assertion, de Beauvoir upended the assumed certainty of sex and gender, and as Judith Butler observed, it was “no longer possible to attribute the values or social functions of women to biological necessity, and neither [could] we refer meaningfully to natural or unnatural gendered behavior: all gender is, by definition, unnatural” (Butler 1986, 35). Once the provocation had been offered that women are made rather than born, the obvious next question was ‘how?’.

During Second Wave feminist art practice in particular, women’s crafts were simultaneously critiqued – as a method by which women were ‘made’ – and celebrated, through the pattern and decoration movement, as a strategy of gendered resistance. Roszika Parker, the psychotherapist and feminist art historian responsible for what would become the essential history of women’s needlework, The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine (1984), redeemed the feminine practice of embroidery from its position as a devalued skill and reconsidered it as a cross-generational language, capable of speaking to and of women’s historical oppression and invisibility. As Griselda Pollack pointed out in her tribute to Parker following her untimely death in 2010, “The impact of Rosie’s radical reconfiguration of the history of embroidery and the meanings of work made in cloth and thread resonated through art schools and museums. Women students, patronized for their so-called feminine work if ever anything associated with “craft,” needle, or fabric was entertained, rather than paint or machines, finally had a context of changing meanings and historical valuations of cloth-based art and a tool to confront the sexist remarks of dismissive tutors. Curators had a theoretical framework for reviewing their collections and exhibiting it anew in ways that allowed cultural history and aesthetic revision to co-emerge” (Pollack in Barnett 2011, 204). Similar approaches were taken by both artists and art historians to other crafts, including knitting, crochet and decoupage, all of which were influential on both feminist art and contemporary art practice more broadly.

The interest in this aesthetic revisioning remains strong. The Subversive Stitch was updated and a new edition published in 2010. Meaghan Shelton’s work has developed in the context of this ongoing conversation about the value of feminine craft. While she is fascinated by the emotional potency of heritage craft techniques, she understands the ambiguous position they assume in the history of invader colonial cultures such as Australia’s. The valorisation of heritage crafts can be quickly subsumed into larger, sinister narratives of ‘settler triumph’. Current discussions about white feminism’s complicity with colonialism signal the risks of ignoring the role that European crafts played in over-writing the rich textiles traditions of first peoples and Indigenous cultures.

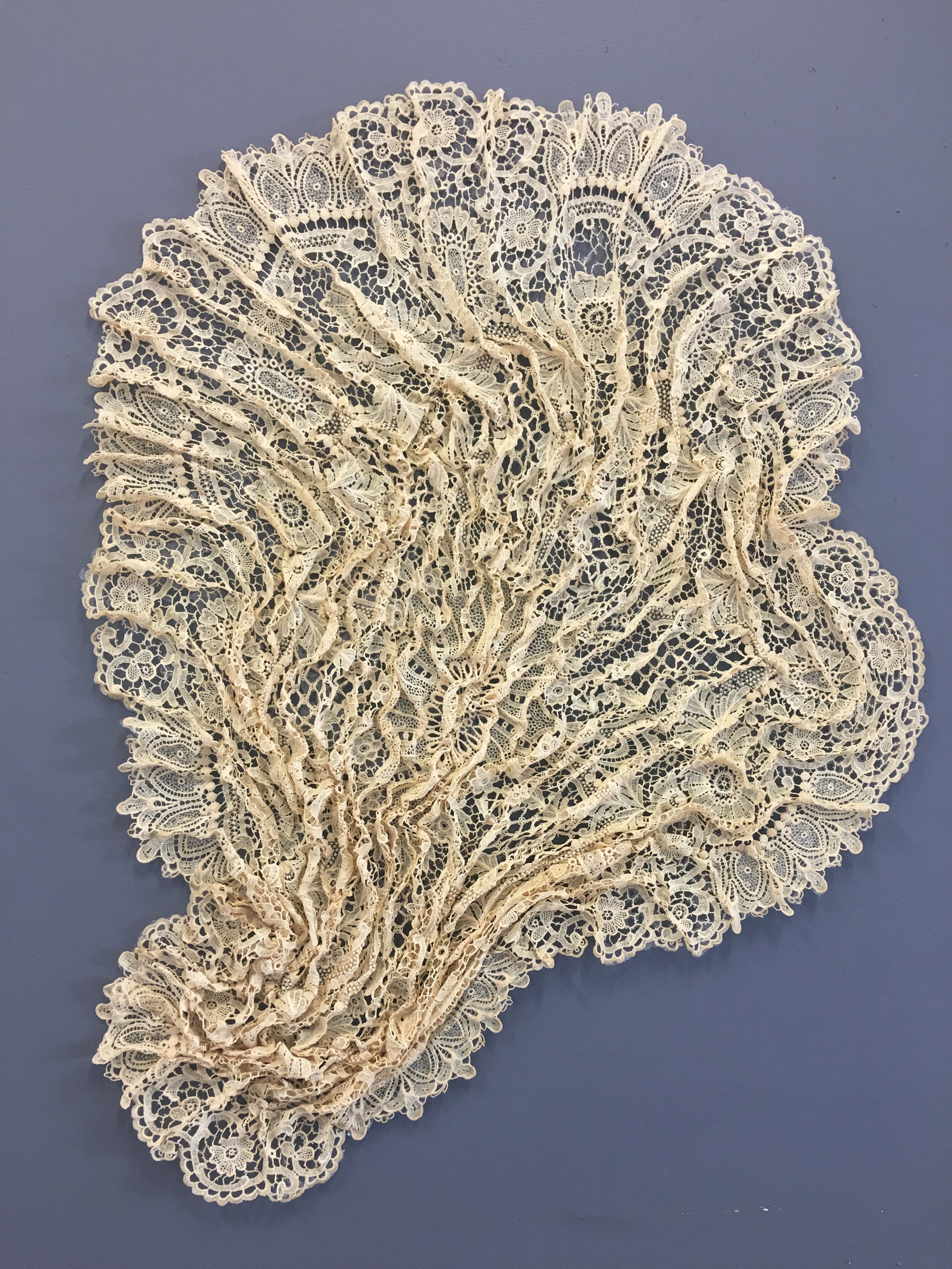

As a consequence, Shelton’s works take their form as aesthetic ghosts and traces. While on one hand, the layering of lace-like forms over dark and foreboding backgrounds speak of personal secrets and family legacies, they can also be interpreted as a visual inference of our historical blind-spots and national shame. Underpinning these images however, is our recognition of the feminised forms as stand-ins for the female body itself. This becomes particularly obvious in the sensuous folds of reclaimed doilies. De Beauvoir spoke of the Sisyphean expectations of repetitive domestic work as a barrier to women having the energy to conceive of wider ambitions, let alone achieve them. Paired with the physical and emotional work of navigating social expectations about the female body, domesticity can become the source of equally exhausting feelings of frustration and impotence.

“The doilies and lace provided a veil to screen those acute feelings of resentment, dissatisfaction and unfulfilled dreams, but also to keep safe those inner thoughts and perceptions not ready to be shown to the world. The latter could refer to the newly found understandings of her body and its responses that a young woman is trying to come to grips with; contemporary culture lacks time, respect or acknowledgement of such things”

Lace and crocheted thread are the leitmotifs of Shelton’s current work. Sections of lace drift across the surfaces of images (such as in Flow or Gatekeeper) or become the focal point of paintings like In Absentia. In Deities, the crocheted doilies lift themselves up from their surfaces and become a constellation of ornate medallions in conversation with each other. Shelton has wistfully discussed the confidence with which her mother approached sewing and how that confidence created respect and intimacy between them. The women whose ‘old knowledge’ informs Shelton’s sensibility as an artist are evoked in the spaces between the delicate patterns of her work. In the making of these works, the artist returns to the moment of embodied learning, when these patterns became part of her sense of self: her girlhood and the subsequent passage through separation, transition and reintegration as a self-aware entity. In the process of making art, Shelton summons up the spectre of the making of women, or their becoming. We are invited to imagine what unspoken and untold stories are woven within them.

By Dr. Courtney Pedersen

Barnett, P. (2011) A Tribute to Rozsika Parker (1945-2010). Textile, 9(2), 200–211.

Butler, J. (1986) Sex and Gender in Simone de Beauvoir’s Second Sex. Yale French Studies: Simone de Beauvoir: Witness to a Century, 72, 35-49

Shelton, M. (2018) Intricate, infinite: Addressing the ineffable aspects of women’s experience through the lens of traditional craft practice. Masters by Research by Creative Works, Queensland University of Technology.

In Absentia XVI, 2016. Oil on canvas. 660 x 660mm

In Absentia XVII 2018, oil on canvas. 660mm x 660mm

Fox, 2017. Doily, sugar starch. 500mm x 500mm

Cyan Fox, 2018. Cyanotype on Arches. 805mm x 753mm

Shield Maiden, 2018. Oil on canvas. 860mm x 860mm

Garden of lost emblems, 2018. Oil on linen. 700mm x 570mm

Night bloom, 2017. Doily, sugar starch. 550mm x 400mm

Confluence, 2018. Cyanotype on Arches. 990mm x 803mm

Ripple 2018, cyanotype on Arches paper. 470mm x 810mm

Deities 2018. Starch, marine ply, enamel, repurposed doilies. 1200mm x 960mm.